Wearing pink badges marked with No. 650, signifying the prisoner number of an unidentified woman in Bagram Jail, the relatives of missing persons on Wednesday gathered in front of Geo TV building for yet another peaceful effort to press for the release of their dear ones.

This time joined by a large number of civil society representatives, members of Jamaat-e-Islami and Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf, the speakers at the protest urged the government to halt all cooperation with the US till the release of all missing persons held in Pakistan and in other countries.

The protesters held placards demanding release of Dr. Aafia Siddiqui and other missing persons and condemned former president Pervez Musharraf for selling Pakistani citizens to other countries. Representatives of Pakistan Professional Forum and common citizens were also part of the protest.

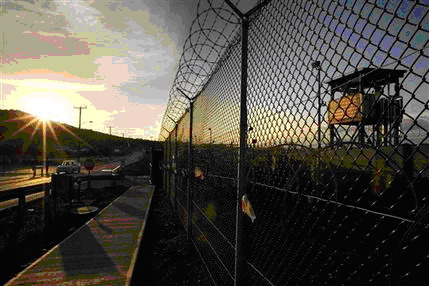

Describing her struggle to reach Prisoner No. 650, she said that prisoners in Guantanamo Bay and those who fled the notorious Bagram Jail confirmed the presence of a woman in Bagram who was brutally tortured and repeatedly raped. “The cries of a helpless woman used to echo in the jail that prompted prisoners to go on a hunger strike,” she said.

Marium said that “There are many Muslim women in the captivity of American forces and are in the same or even worse condition than that of Dr. Aafia,” she said adding that if public remained silent, they would lose their sisters forever. “I beg you to join in my struggle of finding prisoner 650.” She expressed disappointment over the insensitive attitude of the public towards the miserable condition of missing persons. She said that Taliban who were labelled barbaric and uncivilised gave her complete privacy in the prison. “No one used to enter my room without my permission,” she said.

Leading figure in the movement of missing persons, Amina Masood said that it was not difficult to imagine her misery, as she knew that her husband was alive but she was not allowed to even listen to his voice for the past three years. “If our relatives were sold to the American government then the present government should buy them back,” she said begging the leadership to end their ordeal.

She said that the government had promised to constitute a committee to look into the matter yet nothing practical had been done so far. “We do not want any committee, all we want is our dear ones,” she said adding that despite commitments made by the leaders in the government and opposition, the number of missing persons was continuously increasing.

Only a day before, Amina said that a mother of three daughters, Najma Bibi, was taken away by the agencies to an unknown place. She said that Pakistani government should make it clear to the American government that they could not be friends until all missing persons were released.

“The system of missing persons is causing great pain to the citizens of the country and is creating environment of distrust hence it should be completely eliminated,” she said with tears rolling down her eyes.

Dr Shams Hassan Faruqi sits amid his rocks and geological records, shakes his bearded head and stares at me. “I strongly doubt if the children are alive,” he says. “Probably, they have expired.” He says this in a strange way, mournful but resigned, yet somehow he seems oddly unmoved.

As a witness, supposedly, to the mysterious 2008 re-appearance of Aafia Siddiqui – the “most wanted woman in the world”, according to former US attorney general John Ashcroft – I guess this 73-year-old Pakistani geologist is used to the limelight. But the children, I ask him again. What happened to the children?

Dr Faruqi is Aafia Siddiqui’s uncle and he produces a photograph of his niece at the age of 13, picnicking in the Margalla hills above Islamabad, a smiling girl in a yellow shalwar khameez, half-leaning against a tree. She does not look like the stuff of which Al-Qaeda operatives are made.

Yet she is now a semi-icon in Pakistan, a country which may well have been involved in her original kidnapping and which now oh-so-desperately wants her back from an American prison. Her children, weirdly, disconcertingly, have been forgotten.

Aafia Siddiqui’s story is now as famous in Pakistan as it is notorious in a New York City courtroom where her trial for trying to kill an American soldier in the Afghan city of Ghazni in 2008 – she was convicted in February 2010 and faces a minimum of 20 years in prison on just one of the charges against her – is regarded as a symbol of American injustice. “Shame on America,” posters scream in all of Pakistan’s major cities.

She is known as the “grey lady of Bagram”, supposedly tortured for five years in America’s cruel Afghan prison. President Asif Ali Zardari has asked American envoy Richard Holbrooke to repatriate Siddiqui under the Pakistan-US prisoner exchange scheme, while the PM Gilani has dubbed her a “daughter of the nation”. Opposition leader Nawaz Sharif promises to demand her release. But none of them mention the children. Ahmed, Sulieman and Maryam are their names.

Ahmed was returned to Pakistan from Afghanistan in 2008, but DrFaruqi tells me he doesn’t believe for a moment that it is Aafia Siddiqui’s son. “He came here to stay with me, but he said he didn’t know Aafia until he was taken to Ghazni. He said to me: ‘I was in the big earthquake in Afghanistan and my brothers and sisters were killed in their home while I was out fetching water – that’s what saved my life.’ He told me that after the earthquake, he was put in an orphanage in Kabul. He was shown a photograph of my niece Aafia and said he did not know this lady, that he had never seen her before. Then he was taken to Ghazni and told to sit next to this woman – my niece. The boy is intelligent. He is simple. He is honest.”

Ahmed was returned to Pakistan from Afghanistan in 2008, but DrFaruqi tells me he doesn’t believe for a moment that it is Aafia Siddiqui’s son. “He came here to stay with me, but he said he didn’t know Aafia until he was taken to Ghazni. He said to me: ‘I was in the big earthquake in Afghanistan and my brothers and sisters were killed in their home while I was out fetching water – that’s what saved my life.’ He told me that after the earthquake, he was put in an orphanage in Kabul. He was shown a photograph of my niece Aafia and said he did not know this lady, that he had never seen her before. Then he was taken to Ghazni and told to sit next to this woman – my niece. The boy is intelligent. He is simple. He is honest.” All such mysteries require a “story-so-far”. It goes like this.

Aafia Siddiqui, a 38-year-old neuroscientist, an MIT alumna and Brandeis university PhD, disappeared after leaving her sister’s home for Karachi airport in 2003, taking Ahmed, Sulieman and Maryam with her.

The Americans say she was a leading Al-Qaeda operative. So does her ex-husband. She had re-married Ammar al-Baluchi, currently in Guantanamo Bay, a cousin of Ramzi Yousef who was convicted for the 1993 World Trade Centre bombing. Not, you might, say, a healthy curriculum vitae in the West’s obsessive “war on terror”. In 2004, the UN identified her as an Al-Qaeda operative.

But released inmates from the notorious American prison at Bagram near Kabul– where torture is commonplace and at least three prisoners have been murdered – have stated that there was a woman held there, a woman whose nightly screams prompted them to go on hunger strike. She was dubbed the “grey lady of Bagram”. At her New York trial, Siddiqui demanded that Jewish members of the jury be dismissed, she fired her own defence lawyers who said she had become unbalanced after torture; Siddiqui blurted out that she had been tortured in secret prisons before her arrest. “If you were in a secret prison … where children were murdered…” she said.

And so to the town of Ghazni, south of Kabul. It was here that Afghan police stopped her in 2008, carrying a handbag which supposedly contained details of chemical weapons and radiological agents, notes on mass casualty attacks on US targets and maps of Ghazni. American soldiers and FBI agents were summoned to question her and arrived in Ghazni without realising that Siddiqui was in the same room, sitting behind a curtain. According to their evidence, she managed to take one of their M-4 assault rifles and opened fire. She missed but was cut down by two bullets from a 9mm pistol fired by one of the soldiers. Hence the charges. Hence the conviction.

She wasn’t helped by an alleged statement by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed – the man who supposedly planned 9/11 and who is the uncle of her second husband, Ammar al-Baluchi – who claimed that Aafia Siddiqui was a senior Al-Qaeda agent. But then, he’d just been waterboarded 183 times in a month – which hardly makes his evidence, to use a phrase, water-tight.

The questions are obvious. What on earth was a Pakistani American with a Brandeis degree doing in Ghazni with a handbag containing American targets? And why, if her family was so fearful for her, didn’t they report her missing in 2003, go to the press and tell the story of the children? Ahmed – son of Siddiqui or Afghan orphan, depending on your point of view – is now staying with Siddiqui’s sister, Fauzia, in Karachi; but she refuses to let him talk to journalists. The Americans have shown no interest in him – even less in the other two, younger children. Why not?

It’s odd, to say the least, that Dr Faruqi also maintains that in 2008 – before the Ghazni incident – Aafia Siddiqui turned up at his home in the suburbs of Islamabad. “She was wearing a burqa and got out of the car, just outside here,” he says, pointing to the tree-lined street outside his office window. “I only caught sight of her once, and I said ‘You have changed your nose’. But it was her. We talked about the past, her memories, it was her voice. She said the ISI (the Inter-Services Intelligence) had let her come here. She wanted to get away, to go back to Afghanistan where she said the Taliban would protect her. She said that since her arrest, she knew nothing of her children. Someone told her they had been sent to Australia.”

More questions. If Siddiqui was a “ghost prisoner” in Afghanistan, how come she turned up at Dr Faruqi’s home in Islamabad? Why would she wear an Afghan “burqa” in the cosmopolitan capital of her own country? Why did she not talk more about her children? Why could she not show her face to her own uncle? Did she really come to Islamabad?

Fauzia Siddiqui is now touring Pakistan to publicise her sister’s “unfair” trial, her torture at the hands of Americans. Most of the Pakistan press have taken up her story with little critical attention to the allegations against her. She has become a proto-martyr, a martyr-in-being; if her story is comprehensible, it requires a willing suspension of disbelief. But America’s constant protestations of ignorance about her whereabouts before 2008 have an unhappy ring about them.

And the children? Rarely written about in Pakistan, they, too, in a sense, were “disappeared” from the story – until the Afghan President, Hamid Karzai, paid an uneasy visit to Pakistan this week and, according to Fauzia, told the Interior minister, Rehman Malik, that “the children of Aafia Siddiqui will be sent home soon”. Was Karzai referring to the other two children? Or to all three, including the “real” Ahmed? And if Aafia’s two/three children are in Afghanistan, where have they been kept? In an orphanage? In a prison? And who kept them? The Afghans? The Americans?

Many of us are still in a state of shock over the guilty verdict returned on Dr Aafia Siddiqui.

The response from the people of Pakistan was predictable and overwhelming and I salute their spontaneous actions.

From Peshawar to Islamabad, Karachi, Lahore and beyond they marched in their thousands demanding the return of Aafia.

Even some of the US media expressed discomfort over the verdict returned by the jurors … there was a general feeling that something was not right.

Everyone had something to say, everyone that is except the usually verbose US Ambassador Anne Patterson who has spent the last two years briefing against Dr Aafia and her supporters.

This is the same woman who claimed I was a fantasist when I gave a press conference with Tehreek e Insaf leader Imran Khan back in July 2008 revealing the plight of a female prisoner in Bagram called the Grey Lady.

She said I was talking nonsense and stated categorically that the prisoner I referred to as “650” did not exist.

By the end of the month she changed her story and said there had been a female prisoner but that she was most definitely not Dr Aafia Siddiqui.

By that time Aafia had been gunned down at virtually point blank range in an Afghan prison cell jammed full of more than a dozen US soldiers, FBI agents and Afghan police.

Her Excellency briefed the media that the prisoner had wrested an M4 gun from one soldier and fired off two rounds and had to be subdued. The fact these bullets failed to hit a single person in the cell and simply disappeared did not resonate with the diplomat.

In a letter dripping in untruths on August 16 2008 she decried the “erroneous and irresponsible media reports regarding the arrest of Aafia Siddiqui”. She went on to say: “Unfortunately, there are some who have an interest in simply distorting the facts in an effort to manipulate and inflame public opinion. The truth is never served by sensationalism…”

When Jamaat Islami invited me on a national tour of Pakistan to address people about the continued abuse of Dr Aafia and the truth about her incarceration in Bagram, the US Ambassador continued to issue rebuttals. She assured us all that Dr Aafia was being treated humanely had been given consular access as set out in international law … hmm.

Well I have a challenge for Ms Patterson today. I challenge her to repeat every single word she said back then and swear it is the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. As Dr Aafia Siddiqui’s trial got underway, the US Ambassador and some of her stooges from the intelligence world laid on a lavish party at the US Embassy in Islamabad for some hand-picked journalists where I’ve no doubt in between the dancing, drinks and music they were carefully briefed about the so-called facts of the case.

Interesting that some of the potentially incriminating pictures taken at the private party managed to find the Ambassador was probably hoping to minimize the impact the trial would have on the streets of Pakistan proving that, for the years she has been holed up and barricaded behind concrete bunkers and barbed wire, she has learned nothing about this great country of Pakistan or its people.

One astute Pakistani columnist wrote about her: “The respected lady seems to have forgotten the words of her own country’s 16th president Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865): “You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time”. And the people of Pakistan proved they are nobody’s fool and responded to the guilty verdict in New York in an appropriate way.

When injustice is the law it is the duty of everyone to rise up and challenge that injustice in any way possible. The response – so far – has been restrained and measured but it is just the start.

A sentence has yet to be delivered by Judge Richard Berman in May.

Of course there has been a great deal of finger pointing and blame towards the jury in New York who found Dr Aafia guilty of attempted murder.

Observers asked how they could ignore the science and the irrefutable facts … there was absolutely no evidence linking Dr Aafia to the gun, no bullets, no residue from firing it. But I really don’t think we can blame the jurors for the verdict – you see the jury simply could not handle the truth. Had they taken the logical route and gone for the science and the hard, cold, clinical facts it would have meant two things.

It would have meant around eight US soldiers took the oath and lied in court to save their own skins and careers or it would have meant that Dr Aafia Siddiqui was telling the truth. And, as I said before, the jury couldn’t handle the truth. Because that would have meant that the defendant really had been kidnapped, abused, tortured and held in dark, secret prisons by the US before being shot and put on a rendition flight to New York.

It would have meant that her three children – two of them US citizens – would also have been kidnapped, abused and tortured by the US. They say ignorance is bliss and this jury so desperately wanted not to believe that the US could have had a hand in the kidnapping of a five-month -old baby boy, a five-year-old girl and her seven-year-old brother. They couldn’t handle the truth … it is as simple as that. Well I, and many others across the world like me, can’t handle any more lies. America’s reputation is lying in the lowest gutters in Pakistan at the moment and it can’t sink any lower.

The trust has gone, there is only a burning hatred and resentment towards a superpower which sends unmanned drones into villages to slaughter innocents. It is fair to say that America’s goodwill and credibility is all but washed up with most honest, decent citizens of Pakistan.

And I think even Anne Patterson recognizes that fact which is why she is now keeping her mouth shut. If she has any integrity and any self respect left she should stand before the Pakistan people and ask for their forgiveness for the drone murders, the extra judicial killings, the black operations, the kidnapping, torture and rendition of its citizens, the water-boarding, the bribery, the corruption and, not least of all, the injustice handed out to Dr Aafia Siddiqui and her family.

She should then pick up the phone to the US President and tell him to release Aafia and return Pakistan’s most loved, respected and famous daughter and reunite her with the two children who are still missing. Then she should re-read her letter of August 16, 2008 and write another … one of resignation. *

Yvonne Ridley is a patron of Cageprisoners which first brought the plight of Dr Aafia Siddiqui to the world’s attention shortly after her kidnap in March 2003. The award-winning, investigative journalist also co-produced the documentary In Search of Prisoner 650 with film-maker Hassan al Banna Ghani which concluded that the Grey Lady of Bagram was Dr Aafia Siddiqui. Source :

The jury of the Manhattan court found Dr Afia Siddiqui guilty of charges of attempted murder and convicted her. Now on the next date of hearing, the judge after listening to the lawyers shall sentence her.

The conviction prevents the executive branch of the US government from intervening. Therefore no matter how much effort the Pakistani government puts in on a diplomatic level, the conviction cannot be reversed through political or diplomatic means. This is the system of the separation of powers under the US constitution.

So the question is what should be done to bring Dr Afia to Pakistan given that notwithstanding the merits of the case it has become an emotional issue for the people of Pakistan and political parties, putting further pressure on the government to ‘force’ America to return Dr Afia.

Under these circumstances there are three legal options available to the Pakistani government.

Firstly the government can provide or further strengthen the legal team so that they can file an appeal against the conviction and also the forthcoming sentence.

In the appeal the lawyers need to question the inadequacy of the evidence, the extra-legal considerations that may have weighed with the jury and plead other grounds that the US appellate lawyers would be familiar with, based on US jurisprudence and precedents of the US Supreme Court. In this regard the government must make available to Dr Afia any additional specialised appellate lawyer so that from a legal point of view all necessary grounds are raised and well pleaded.

The second legal option to bring back Dr Afia would be for the US president to pardon her. The US president has the legal competence to pardon both, the conviction and the sentence.

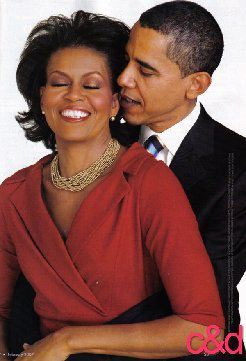

This power is exercisable normally by all heads of state and is part of the executive competence of the president’s office. The Pakistan government through the US ambassador or State Department can lobby that in this particular case circumstances warrant that President Obama should exercise his presidential discretion to grant a pardon as this would have a strong bearing on improving relations between the people of Paksitan and the US government.

This may not be an easy route as President Obama will feel the domestic pressure not to extend pardon to a woman who was facing serious charges. With the Department of Justice and the attorney general’s office taking the decision to prosecute her and incurring expenses on the said trial, it may feel compelled to disregard the initial decision-making of the executive on the basis of political considerations alone.

The third option to bring back Dr Afia is that she can be transferred to Pakistan to complete her sentence here.

This option has not been explored by the Pakistani government and perhaps even the US government so far. Neither has it been debated in parliament or deliberated in a parliamentary committee.

There exists in Pakistan a specialised statute called the Transfer of Offenders Ordinance 2002. This ordinance as a prerequisite only requires that Pakistan should have a bilateral agreement with US, for the mutual transfer of offenders. Pakistan may already have this agreement and if not it can be made and executed without delay.

The advantage will accrue to both countries. Offenders in Pakistan can be transferred to the US, and offenders in the US can be transferred to Pakistan to complete their sentences. It is a kind of post-conviction extradition. This way the foreign country can fulfil its constitutional mandate of bringing a perpetrator to justice by obtaining a conviction successfully and, thereafter sending him to his country of origin, for completion of the sentence.

The power to transfer an offender exists in US law under Title 18, Part III, Chapter 306, Section 4100 of the US Code, which states “an offender may be transferred from the United States pursuant to this chapter only to a country of which the offender is a citizen or national”.

Once she is transferred to Pakistan to complete her sentence under the above-mentioned ordinance of 2002 or under US law, then her house can also be notified as a sub jail, or she could be put in a separate premises in Pakistan somewhere. She would be entitled to remissions as per Pakistan’s jail manual.

Although she would continue to be in custody to complete the sentence the fact that she will be doing so in Pakistan would be extremely reassuring to the people of Pakistan and would also be taken as a very positive gesture by the US administration given the circumstances. This would hopefully resolve tensions surrounding this issue between the people of Pakistan and the US administration.

This option will result in a win-win situation for all concerned. Firstly the US government would have fulfilled its mandate of bringing Dr Afia to justice, secondly the Pakistani government would have brought back Dr Afia to Pakistan and thirdly Dr Afia would be close to her relatives and friends.

Aafia Siddiqui may be a minor light in the constellation of alleged al-Qaeda operatives, but her New York City trial may be a test case for the way justice is meted out to one of the major figures accused of running the terror organization.

Siddiqui is a US trained, Pakistani neuroscientist charged with attempted murder for allegedly firing an M-4 automatic rifle at a group of U.S. soldiers and FBI agents in Afghanistan. Her case has been major news in much of the Muslim world — and a crush of journalists from Pakistan have been struggling to gain access to a trial hemmed in by security-conscious New York City officials.

How the foreign press is able to follow the court proceedings — and thus perceive the fairness of the trial — will have an impact on upcoming high-profile terrorism trials like that of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four other suspected 9/11 plotters, likely to be held in the same courthouse as the Siddiqui case.

“If we were able to file a transcript of the proceedings they’d probably print it,” Iftikhar Ali, a reporter with the Associated Press of Pakistan, said of the Siddiqui trial. “That’s how much interest there is in this case.” But Ali, like many other reporters from overseas, has been hampered in gaining access to the live proceedings.

Journalists from Pakistan on assignment in New York have been largely excluded from the courtroom. Because of tight restrictions observed by the presiding Judge Richard Berman, not a single Pakistani reporter had been granted a press credential when opening statements began on January 26, 2010. They were instead sent to an overflow courtroom to watch the proceedings via video link.

In the overflow room I met journalists from Pakistan with United Nations and U.S. State Department issued press credentials. They work for some of the biggest outlets in their countries, including BBC Urdu, the Associated Press in Pakistan, Jang, Dawn, Geo and Aaj TV. None were issued credentials for the trial, though some had applied weeks ago.

We watched the proceedings on a flat screen television. The view didn’t include any of the exhibits being offered into evidence, among them multiple diagrams of the scene of the shooting and incriminating documents allegedly written by Siddiqui.

At one point a key government eyewitness stepped off the witness stand and out of range of both the camera and microphone to use a visual aid to demonstrate where he was during the shooting. He was permitted to give much of his testimony off camera.

Ali, who has been at the court every day of the trial — including jury selection — was granted access to the main courtroom for about five minutes on the first day, but was escorted out when court security guards realized he was not on the list of approved media. At the time the only other occupants of the four-row press box, which covers half the available seating in the courtroom with room for about 20 individuals, were one each from the The New York Times, The New York Post and the New York Daily News. The court has officially recognized only media who carry New York Police Department issued press passes, traditionally reserved for reporters who regularly cover crime scenes and certain public events in the city. Out of the approximately 30 such individuals from U.S. news outlets who were eligible to attend the trial, most were not present for opening statements.

“We’ve been coming to all the pretrial hearings and we were never told there was going to be a different system for the trial. We were told the press will be allowed,” Ayesha Tanzeem, a journalist with Voice of America Urdu said.

Individuals in the overflow room, including the Pakistani journalists, were for the first time ushered into the main courtroom during the afternoon session. But with the exception of a BBC Urdu reporter and a Samaa TV reporter who received official passes, none have been granted a press credential that would guarantee them a seat on future days.

The decision to accept solely the NYPD pass for the Siddiqui trial came from the judge’s chambers, says Elly Harrold of the District Executive’s office, the administrative arm at the federal courthouse. “Of course there are exceptions,” Harrold said, “but I’m not at liberty to discuss that.”

Although Siddiqui is not charged with any terrorism-related crime, security concerns are paramount though the procedures seem to be unevenly enforced. During the lunch break on the first day of the Siddiqui trial a group of Muslim men praying in the waiting areas outside the courtroom were afterwards asked to leave the floor. That prevented them from securing a place in line for the afternoon session. Several Muslim women in hijabs were also given similar instructions, but others in the same area, dressed in business attire, including this reporter, were permitted to stay. On the second day of the trial metal detectors were posted outside the courtroom and individuals were asked for photo identification and their names and addresses were logged by court security officers. At the close of proceedings on January 21, defense attorney Charles Swift protested the practice. “The suggestion is that the gallery may be a threat,” said Swift, calling the measure “highly prejudicial.”

The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui

The Guardian, Tuesday November 24 2009

The Guardian, Tuesday November 24 2009

Declan Walsh

on a hot summer morning 18 months ago a team of four Americans two FBI agents and two army officers rolled into Ghazni, a dusty town 50 miles south of Kabul. They had come to interview two unusual prisoners: a woman in a burka and her 11-year-old son, arrested the day before.

Afghan police accused the mysterious pair of being suicide bombers. What interested the Americans, though, was what they were carrying: notes about a “mass casualty attack” in the US on targets including the Statue of Liberty and a collection of jars and bottles containing “chemical and gel substances”.

At the town police station the Americans were directed into a room where, unknown to them, the woman was waiting behind a long yellow curtain. One soldier sat down, laying his M-4 rifle by his foot, next to the curtain.

Afghan police accused the mysterious pair of being suicide bombers. What interested the Americans, though, was what they were carrying: notes about a “mass casualty attack” in the US on targets including the Statue of Liberty and a collection of jars and bottles containing “chemical and gel substances”.

At the town police station the Americans were directed into a room where, unknown to them, the woman was waiting behind a long yellow curtain. One soldier sat down, laying his M-4 rifle by his foot, next to the curtain.

Moments later it twitched back.

The woman was standing there, pointing the officer’s gun at his head. A translator lunged at her, but too late. She fired twice, shouting “Get the fuck out of here!” and “Allahu Akbar!” Nobody was hit. As the translator wrestled with the woman, the second soldier drew his pistol and fired, hitting her in the abdomen. She went down, still kicking and shouting that she wanted “to kill Americans”. Then she passed out.

Whether this extraordinary scene is fiction or reality will soon be decided thousands of miles from Ghazni in a Manhattan courtroom. The woman is Dr Aafia Siddiqui, a Pakistani neuroscientist and mother of three. The description of the shooting, in July 2008, comes from the prosecution case,

which Siddiqui disputes. What isn’t in doubt is that there was an incident, and that she was shot, after which she was helicoptered to Bagram air field where medics cut her open from breastplate to bellybutton, searching for bullets. Medical records show she barely survived. Seventeen days later, still recovering, she was bundled on to an FBI jet and flown to New York where she now faces seven counts of assault and attempted murder. If convicted, the maximum sentence is life in prison.

The prosecution is but the latest twist in one of the most intriguing

episodes of America’s “war on terror”. At its heart is the MIT-educated Siddiqui, once declared the world’s most wanted woman. In 2003 she mysteriously vanished for five years, during which time she was variously dubbed the “Mata Hari of al-Qaida” or the “Grey Lady of Bagram”, an iconic victim of American brutality.

Yet only the narrow circumstances of her capture did she open fire on the US soldier? are at issue in the New York court case. Fragile-looking, and often clad in a dark robe and white headscarf, Siddiqui initially pleaded not guilty, insisting she never touched the soldier’s gun. Her lawyers say the prosecution’s dramatic version of the shooting is untrue. Now, after months of pre-trial hearings, she appears bent on scuppering the entire process.

During a typically stormy hearing on Nov 19, 2009, Siddiqui interrupted the judge, rebuked her own lawyers and made strident appeals to the packed courthouse. “I am boycotting this trial,” she declared. “I am innocent of all the charges and I can prove it, but I will not do it in this court.”

The woman was standing there, pointing the officer’s gun at his head. A translator lunged at her, but too late. She fired twice, shouting “Get the fuck out of here!” and “Allahu Akbar!” Nobody was hit. As the translator wrestled with the woman, the second soldier drew his pistol and fired, hitting her in the abdomen. She went down, still kicking and shouting that she wanted “to kill Americans”. Then she passed out.

Whether this extraordinary scene is fiction or reality will soon be decided thousands of miles from Ghazni in a Manhattan courtroom. The woman is Dr Aafia Siddiqui, a Pakistani neuroscientist and mother of three. The description of the shooting, in July 2008, comes from the prosecution case,

which Siddiqui disputes. What isn’t in doubt is that there was an incident, and that she was shot, after which she was helicoptered to Bagram air field where medics cut her open from breastplate to bellybutton, searching for bullets. Medical records show she barely survived. Seventeen days later, still recovering, she was bundled on to an FBI jet and flown to New York where she now faces seven counts of assault and attempted murder. If convicted, the maximum sentence is life in prison.

The prosecution is but the latest twist in one of the most intriguing

episodes of America’s “war on terror”. At its heart is the MIT-educated Siddiqui, once declared the world’s most wanted woman. In 2003 she mysteriously vanished for five years, during which time she was variously dubbed the “Mata Hari of al-Qaida” or the “Grey Lady of Bagram”, an iconic victim of American brutality.

Yet only the narrow circumstances of her capture did she open fire on the US soldier? are at issue in the New York court case. Fragile-looking, and often clad in a dark robe and white headscarf, Siddiqui initially pleaded not guilty, insisting she never touched the soldier’s gun. Her lawyers say the prosecution’s dramatic version of the shooting is untrue. Now, after months of pre-trial hearings, she appears bent on scuppering the entire process.

During a typically stormy hearing on Nov 19, 2009, Siddiqui interrupted the judge, rebuked her own lawyers and made strident appeals to the packed courthouse. “I am boycotting this trial,” she declared. “I am innocent of all the charges and I can prove it, but I will not do it in this court.”

Previously she had tried to fire her lawyers due to their Jewish background (she once wrote to the court that Jews are “cruel, ungrateful, back-stabbing” people) and demanded to speak with President Obama for the purpose of “making peace” with the Taliban. This time, though, she was ejected from the courtroom for obstruction. “Take me out. I’m not coming back,” she said defiantly.

The trial, due to start in January, is just one piece of a much larger

puzzle. It is a tale of spies and militants, disappearance and deception, which has played out in the shadowlands of Pakistan and Afghanistan since 2001. In search of answers I criss-crossed Pakistan, tracking down Siddiqui’s relatives, retired ministers, shadowy spy types and pamphleteers.

The trial, due to start in January, is just one piece of a much larger

puzzle. It is a tale of spies and militants, disappearance and deception, which has played out in the shadowlands of Pakistan and Afghanistan since 2001. In search of answers I criss-crossed Pakistan, tracking down Siddiqui’s relatives, retired ministers, shadowy spy types and pamphleteers.

The truth was maddeningly elusive. But it all started in Karachi, the

sprawling port city on the Arabian Sea where Siddiqui was born 37 years ago.

Her parents were Pakistani strivers middle-class folk with strong faith in Islam and education. Her father, Mohammad, was an English-trained doctor; hermother, Ismet, befriended the dictator General Zia ul-Haq. Aafia was a smart teenager, and in 1990 followed her older brother to the US. Impressive grades won her admission to the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of

Technology and, later, Brandeis University, where she graduated in cognitive neuroscience. In 1995 she married a young Karachi doctor, Amjad Khan; a year later their first child, Ahmed, was born.

Siddiqui was also an impassioned Muslim activist. In Boston she campaigned for Afghanistan, Bosnia and Chechnya; she was particularly affected by graphic videos of pregnant Bosnian women being killed. She wrote emails, held fundraisers and made forceful speeches at her local mosque. But the charities she worked with had sharp edges. The Nairobi branch of one, Mercy International Relief Agency, was linked to the 1998 US embassy bombings in

east Africa; three other charities were later banned in the US for their links to al-Qaida.

The September 11 2001 attacks marked a turning point in Siddiqui’s life. In May 2002 the FBI questioned her and her husband about some unusual internet purchases they had made: about $10,000 worth of night-vision goggles, body armour and 45 military-style books including The Anarchist’s Arsenal. (Khan

said he bought the equipment for hunting and camping expeditions.) Their marriage started to crumble. A few months later the couple returned to Pakistan and divorced that August, two weeks before the birth of their third child, Suleman.

On Christmas Day 2002 Siddiqui left her three children with her mother in Pakistan and returned to the US, ostensibly to apply for academic jobs.

sprawling port city on the Arabian Sea where Siddiqui was born 37 years ago.

Her parents were Pakistani strivers middle-class folk with strong faith in Islam and education. Her father, Mohammad, was an English-trained doctor; hermother, Ismet, befriended the dictator General Zia ul-Haq. Aafia was a smart teenager, and in 1990 followed her older brother to the US. Impressive grades won her admission to the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of

Technology and, later, Brandeis University, where she graduated in cognitive neuroscience. In 1995 she married a young Karachi doctor, Amjad Khan; a year later their first child, Ahmed, was born.

Siddiqui was also an impassioned Muslim activist. In Boston she campaigned for Afghanistan, Bosnia and Chechnya; she was particularly affected by graphic videos of pregnant Bosnian women being killed. She wrote emails, held fundraisers and made forceful speeches at her local mosque. But the charities she worked with had sharp edges. The Nairobi branch of one, Mercy International Relief Agency, was linked to the 1998 US embassy bombings in

east Africa; three other charities were later banned in the US for their links to al-Qaida.

The September 11 2001 attacks marked a turning point in Siddiqui’s life. In May 2002 the FBI questioned her and her husband about some unusual internet purchases they had made: about $10,000 worth of night-vision goggles, body armour and 45 military-style books including The Anarchist’s Arsenal. (Khan

said he bought the equipment for hunting and camping expeditions.) Their marriage started to crumble. A few months later the couple returned to Pakistan and divorced that August, two weeks before the birth of their third child, Suleman.

On Christmas Day 2002 Siddiqui left her three children with her mother in Pakistan and returned to the US, ostensibly to apply for academic jobs.

During the 10-day trip, however, Siddiqui did something controversial: she opened a post box in the name of Majid Khan, an alleged al-Qaida operative accused of plotting to blow up petrol stations in the Baltimore area. The post box, prosecutors later said, was to facilitate his entry into the US.

Six months after her divorce, she married Ammar al-Baluchi, a nephew of the 9/11 mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, at a small ceremony near Karachi. Siddiqui’s family denies the wedding took place, but it has been confirmed

by Pakistani and US intelligence, al-Baluchi’s relatives and, according to FBI interview reports recently filed in court, Siddiqui herself. At any rate, it was a short-lived honeymoon.

In March 2003 the FBI issued a global alert for Siddiqui and her ex-husband, Amjad Khan. Then, a few weeks later, she vanished. According to her family, she climbed into a taxi with her three children six-year-old Ahmed, four-year-old Mariam and six-month old Suleman and headed for Karachi airport. They never made it. (Khan, on the other hand, was interviewed by the FBI in Pakistan, and subsequently released.)

Initially it was presumed that Siddiqui had been picked up by Pakistan’s ISI at the behest of the CIA. The theory seemed to be confirmed by American media reports that Siddiqui’s name

had been given up by Mohammed, the 9/11 instigator, who was captured three weeks earlier. (If so, Mohammed was probably speaking under duress the CIA waterboarded him 183 times that month.)

There are several accounts of what happened next. According to the US government, Siddiqui was at large, plotting mayhem on behalf of Osama bin Laden. In May 2004 the US attorney general, John Ashcroft, listed her among the seven “most wanted” al-Qaida fugitives. “Armed and dangerous,” he said, describing the Karachi woman as a terrorist “facilitator” who was willing to use her education against America. “Al-Qaida Mom” ran the headline in the

New York Post.

But Siddiqui’s family and supporters tell a different story. Instead of plotting attacks, they say, Siddiqui spent the missing five years at the dreaded Bagram detention centre, north of Kabul, where she suffered unspeakable horrors. Yvonne Ridley, the British journalist turned Muslim campaigner, insists she is the “Grey Lady of Bagram” a ghostly female detainee who kept prisoners awake “with her haunting sobs and piercing screams”. In 2005 male prisoners were so agitated by her plight, she says, that they went on hunger strike for six days.

For campaigners such as Ridley, Siddiqui has become emblematic of dark American practices such as abduction, rendition and torture. “Aafia has iconic status in the Muslim world. People are angry with American imperialism and domination,” she told me.

But every major security agency of the US government army, FBI, CIA denies having held her. Last year the US ambassador to Islamabad, Anne Patterson, went even further. She stated that Siddiqui was not in US custody “at any time” prior to July 2008. Her language was unusually categoric.

To reconcile these accounts I flew to Siddiqui’s hometown of Karachi. The family lives in a spacious house with bougainvillea-draped walls in Gulshan Iqbal, a smart middle-class neighbourhood. Inside I took breakfast with her

sister, Fowzia, on a patio overlooking a toy-strewn garden.

As servants brought piles of paratha (fried bread), Fowzia produced photos of a smiling young woman whom she described as the victim of aninternationalconspiracy. The US had been abusing her sister in Bagram, she said, then produced her for trial as part of a gruesome justice pageant. “As far as I’m concerned this trial [in New York] is just a great drama. They write the script as they go. I’ve stopped asking questions,” she said resignedly.

But Fowzia, a Harvard-educated neurologist, was frustratingly short on hard information. She responded to questions about Aafia’s whereabouts between 2003 and 2008 with cryptic cliches. “It’s not that we don’t know. It’s that we don’t want to know,” she said. And she blamed reports of al-Qaida links

on a malevolent American press. “Half of them work for the CIA,” she said.

The odd thing, though, was that the person who might unlock the entire mystery was living in the same house. After being captured with his mother in Ghazni last year, 11-year-old Ahmed Siddiqui was flown back to Pakistan on orders from the Afghan president, Karzai. Since then he has been living with his aunt Fowzia. Yet she has forbidden him from speaking with the press even with Yvonne Ridley because, she told me, he was too traumatised.

“You tell him to do something but he just stands there, staring at the TV,” she said, sighing heavily. But surely, I insisted, after 15 months at home the boy must have divulged some clue about the missing years?

Fowzia’s tone hardened. “Ahmed’s not allowed to speak to the press. That was part of the deal when they gave him to us,” she said firmly.

“Who are they?” I asked.

She waved a finger in the air. “The network. Those who brought him here.”

Moments later Fowzia excused herself. The interview was over. As she walked me to the gate, I was struck by another omission: Fowzia had barely mentioned Ahmed’s 11-year-old sister, Mariam, or his seven-year-old brother, Suleman, who are still missing. Amid the hullabaloo about their imprisoned mother, Aafia’s children seemed to be strangely forgotten.

That night I went to see Siddiqui’s ex-husband, Amjad Khan. He ushered me through a deathly quiet house into an upstairs room where we sat cross-legged on the floor. He had a soft face under the curly beard that is worn by devout Muslims. I recounted what Fowzia told me. He sighed and shook his head. “It’s all a smokescreen,” he said. “She’s trying to divert your attention.”

The truth of the matter, he said, was that Siddiqui had never been sent to Bagram. Instead she spent the five years on the run, living clandestinely with her three children, under the watchful eye of Pakistani intelligence.

Six months after her divorce, she married Ammar al-Baluchi, a nephew of the 9/11 mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, at a small ceremony near Karachi. Siddiqui’s family denies the wedding took place, but it has been confirmed

by Pakistani and US intelligence, al-Baluchi’s relatives and, according to FBI interview reports recently filed in court, Siddiqui herself. At any rate, it was a short-lived honeymoon.

In March 2003 the FBI issued a global alert for Siddiqui and her ex-husband, Amjad Khan. Then, a few weeks later, she vanished. According to her family, she climbed into a taxi with her three children six-year-old Ahmed, four-year-old Mariam and six-month old Suleman and headed for Karachi airport. They never made it. (Khan, on the other hand, was interviewed by the FBI in Pakistan, and subsequently released.)

Initially it was presumed that Siddiqui had been picked up by Pakistan’s ISI at the behest of the CIA. The theory seemed to be confirmed by American media reports that Siddiqui’s name

had been given up by Mohammed, the 9/11 instigator, who was captured three weeks earlier. (If so, Mohammed was probably speaking under duress the CIA waterboarded him 183 times that month.)

There are several accounts of what happened next. According to the US government, Siddiqui was at large, plotting mayhem on behalf of Osama bin Laden. In May 2004 the US attorney general, John Ashcroft, listed her among the seven “most wanted” al-Qaida fugitives. “Armed and dangerous,” he said, describing the Karachi woman as a terrorist “facilitator” who was willing to use her education against America. “Al-Qaida Mom” ran the headline in the

New York Post.

But Siddiqui’s family and supporters tell a different story. Instead of plotting attacks, they say, Siddiqui spent the missing five years at the dreaded Bagram detention centre, north of Kabul, where she suffered unspeakable horrors. Yvonne Ridley, the British journalist turned Muslim campaigner, insists she is the “Grey Lady of Bagram” a ghostly female detainee who kept prisoners awake “with her haunting sobs and piercing screams”. In 2005 male prisoners were so agitated by her plight, she says, that they went on hunger strike for six days.

For campaigners such as Ridley, Siddiqui has become emblematic of dark American practices such as abduction, rendition and torture. “Aafia has iconic status in the Muslim world. People are angry with American imperialism and domination,” she told me.

But every major security agency of the US government army, FBI, CIA denies having held her. Last year the US ambassador to Islamabad, Anne Patterson, went even further. She stated that Siddiqui was not in US custody “at any time” prior to July 2008. Her language was unusually categoric.

To reconcile these accounts I flew to Siddiqui’s hometown of Karachi. The family lives in a spacious house with bougainvillea-draped walls in Gulshan Iqbal, a smart middle-class neighbourhood. Inside I took breakfast with her

sister, Fowzia, on a patio overlooking a toy-strewn garden.

As servants brought piles of paratha (fried bread), Fowzia produced photos of a smiling young woman whom she described as the victim of aninternationalconspiracy. The US had been abusing her sister in Bagram, she said, then produced her for trial as part of a gruesome justice pageant. “As far as I’m concerned this trial [in New York] is just a great drama. They write the script as they go. I’ve stopped asking questions,” she said resignedly.

But Fowzia, a Harvard-educated neurologist, was frustratingly short on hard information. She responded to questions about Aafia’s whereabouts between 2003 and 2008 with cryptic cliches. “It’s not that we don’t know. It’s that we don’t want to know,” she said. And she blamed reports of al-Qaida links

on a malevolent American press. “Half of them work for the CIA,” she said.

The odd thing, though, was that the person who might unlock the entire mystery was living in the same house. After being captured with his mother in Ghazni last year, 11-year-old Ahmed Siddiqui was flown back to Pakistan on orders from the Afghan president, Karzai. Since then he has been living with his aunt Fowzia. Yet she has forbidden him from speaking with the press even with Yvonne Ridley because, she told me, he was too traumatised.

“You tell him to do something but he just stands there, staring at the TV,” she said, sighing heavily. But surely, I insisted, after 15 months at home the boy must have divulged some clue about the missing years?

Fowzia’s tone hardened. “Ahmed’s not allowed to speak to the press. That was part of the deal when they gave him to us,” she said firmly.

“Who are they?” I asked.

She waved a finger in the air. “The network. Those who brought him here.”

Moments later Fowzia excused herself. The interview was over. As she walked me to the gate, I was struck by another omission: Fowzia had barely mentioned Ahmed’s 11-year-old sister, Mariam, or his seven-year-old brother, Suleman, who are still missing. Amid the hullabaloo about their imprisoned mother, Aafia’s children seemed to be strangely forgotten.

That night I went to see Siddiqui’s ex-husband, Amjad Khan. He ushered me through a deathly quiet house into an upstairs room where we sat cross-legged on the floor. He had a soft face under the curly beard that is worn by devout Muslims. I recounted what Fowzia told me. He sighed and shook his head. “It’s all a smokescreen,” he said. “She’s trying to divert your attention.”

The truth of the matter, he said, was that Siddiqui had never been sent to Bagram. Instead she spent the five years on the run, living clandestinely with her three children, under the watchful eye of Pakistani intelligence.

He told me they shifted between Quetta in Baluchistan province, Iran and the Karachi house I had visited earlier that day. It was a striking explanation.

When I asked for proof, he started at the beginning.

Their parents, who arranged the marriage, thought them a perfect match. The couple had a lot in common education, wealth and a love for conservative Islam. They were married over the phone; soon after Khan moved to America.

Their parents, who arranged the marriage, thought them a perfect match. The couple had a lot in common education, wealth and a love for conservative Islam. They were married over the phone; soon after Khan moved to America.

But his new wife was a more fiery character than he wished. “She was so pumped up about jihad,” he said.

Six months into the marriage, Siddiqui demanded the newlyweds move to Bosnia. Khan refused, and grew annoyed at her devotion to activist causes.

Six months into the marriage, Siddiqui demanded the newlyweds move to Bosnia. Khan refused, and grew annoyed at her devotion to activist causes.

During a furious argument one night, he told me, he flung a milk bottle at his wife that split her lip.

After 9/11 Aafia insisted on returning to Pakistan, telling her husband that the US government was forcibly converting Muslim children to Christianity.

After 9/11 Aafia insisted on returning to Pakistan, telling her husband that the US government was forcibly converting Muslim children to Christianity.

Later that winter she pressed him to go on “jihad” to Afghanistan, where she had arranged for them to work in a hospital in Zabul province. Khan refused, sparking a vicious row. “She went hysterical, beating her hands on my chest, asking for divorce,” he recalled.

After Siddiqui disappeared in March 2003, Khan started to worry for his children he had never seen his youngest son, Suleman. But he was reassured that they were still in Pakistan through three sources. He hired people to watch her house and they reported her comings and goings. His family was also briefed by ISI officials who said they were following her movements, he said. (Khan named an ISI brigadier whom I later contacted; he declined to speak).

Most strikingly, Khan claimed to have seen his ex-wife with his own eyes. In April 2003, he said, the ISI asked him to identify his ex-wife as she got off a flight from Islamabad, accompanied by her son. Two years later he spotted her again in a Karachi traffic jam. But he never went public with the information. “I wanted to protect her, for the sake of my children,” he said.

Khan’s version of events has enraged his ex-wife’s family. Fowzia has launched a 500m rupees (£360,000) defamation law suit, while regularly attacking him in the press as a wifebeater set on “destroying” her family.

After Siddiqui disappeared in March 2003, Khan started to worry for his children he had never seen his youngest son, Suleman. But he was reassured that they were still in Pakistan through three sources. He hired people to watch her house and they reported her comings and goings. His family was also briefed by ISI officials who said they were following her movements, he said. (Khan named an ISI brigadier whom I later contacted; he declined to speak).

Most strikingly, Khan claimed to have seen his ex-wife with his own eyes. In April 2003, he said, the ISI asked him to identify his ex-wife as she got off a flight from Islamabad, accompanied by her son. Two years later he spotted her again in a Karachi traffic jam. But he never went public with the information. “I wanted to protect her, for the sake of my children,” he said.

Khan’s version of events has enraged his ex-wife’s family. Fowzia has launched a 500m rupees (£360,000) defamation law suit, while regularly attacking him in the press as a wifebeater set on “destroying” her family.

“Marrying him was Aafia’s biggest mistake,” she told me. Khan says it is a ploy to silence him in the media and take away his children.

Khan’s explanation is bolstered by the one person who claims to have met the missing neuroscientist between 2003 and 2008 her uncle, Shams ul-Hassan Faruqi. Back in Islamabad, I went to see him.

A sprightly old geologist, Faruqi works from a cramped office filled with coloured rocks and dusty computers. Over tea and biscuits he described a strange encounter with his niece in January 2008, six months before she was captured in Afghanistan.

It started, he said, when a white car carrying a burka-clad woman pulled up outside his gate. Beckoning him to approach, he recognised her by her voice.

Khan’s explanation is bolstered by the one person who claims to have met the missing neuroscientist between 2003 and 2008 her uncle, Shams ul-Hassan Faruqi. Back in Islamabad, I went to see him.

A sprightly old geologist, Faruqi works from a cramped office filled with coloured rocks and dusty computers. Over tea and biscuits he described a strange encounter with his niece in January 2008, six months before she was captured in Afghanistan.

It started, he said, when a white car carrying a burka-clad woman pulled up outside his gate. Beckoning him to approach, he recognised her by her voice.

“Uncle, I am Aafia,” he recalled her saying. But she refused to leave the car and insisted they move to the nearby Taj Mahal restaurant to talk. Amid whispers, her story tumbled out.

Siddiqui told him she had been in both Pakistani and American captivity since 2003, but was vague on the details. “I was in the cells but I don’t know in which country, or which city. They kept shifting me,” she said. Now she had been set free but remained under the thumb of intelligence officials based in Lahore. They had given her a mission: to infiltrate al-Qaida in Pakistan. But, Siddiqui told her uncle, she was afraid and wanted out. She begged him to smuggle her into Afghanistan into the hands of the Taliban. “That was her main point,” he recalled. “She said: ‘I will be safe with the

Taliban.’”

That night, Siddiqui slept at a nearby guesthouse, and stayed with her uncle the next day. But she refused to remove her burka. Faruqi said he caught a glimpse of her just once, while eating, and thought her nose had been altered. “I asked her, ‘Who did plastic surgery on your face?’ She said, ‘nobody’.”

On the third day, Siddiqui vanished again.

Siddiqui told him she had been in both Pakistani and American captivity since 2003, but was vague on the details. “I was in the cells but I don’t know in which country, or which city. They kept shifting me,” she said. Now she had been set free but remained under the thumb of intelligence officials based in Lahore. They had given her a mission: to infiltrate al-Qaida in Pakistan. But, Siddiqui told her uncle, she was afraid and wanted out. She begged him to smuggle her into Afghanistan into the hands of the Taliban. “That was her main point,” he recalled. “She said: ‘I will be safe with the

Taliban.’”

That night, Siddiqui slept at a nearby guesthouse, and stayed with her uncle the next day. But she refused to remove her burka. Faruqi said he caught a glimpse of her just once, while eating, and thought her nose had been altered. “I asked her, ‘Who did plastic surgery on your face?’ She said, ‘nobody’.”

On the third day, Siddiqui vanished again.

Amid the blizzard of allegations about Siddiqui, the most crucial voice is yet to be heard her own. The trial, due to start in January, has suffered numerous delays. The longest was due to a six-month psychiatric evaluation triggered by defence claims that Siddiqui was “going crazy” prone to crying fits and hallucinations involving flying infants, dark angels and a dog in her cell. “She’s in total psychic pain,” said her lawyer, Dawn Cardi, claiming that she was unfit to stand trial.

But at the Texas medical centre where the tests took place, Siddiqui refused to co-operate. “I can’t hear you. I’m not listening,” she told one doctor, sitting on the floor with her fingers in her ears. Others reported that she refused to speak with Jews, that she manipulated health workers and perceived herself to “be a martyr rather than a prisoner”. Last July three of four experts determined she was malingering faking a psychiatric illness to avoid an undesirable outcome. “She is an intelligent and at times manipulative woman who showed goal-directed and rational thinking,” reported Dr Sally Johnson.

Judge Richard Berman ruled that Siddiqui “may have some mental health issues” but was competent to stand trial.

Back in Pakistan Siddiqui has become a cause celebre. Newspapers write unquestioningly about her “torture”, parliament has passed resolutions, placard-waving demonstrators pound the streets and the government is spending $2m on a top-flight defence. High-profile supporters include the former cricketer Imran Khan and the Taliban leader Hakumullah Mehsud who has affectionately described Siddiqui as a “sister in Islam”.

The unquestioning support is a product of public fury at US-orchestrated “disappearances”, of which there have been hundreds in Pakistan, and deep scepticism about the American account of her capture. Few Pakistanis believe a frail 5ft 3in, 40kg woman could disarm an American soldier; fewer still think she would be carrying bomb booklets, chemicals and target lists.

But there are critics, too, albeit silent ones. A Musharraf-era minister with previous oversight of Siddiqui’s case told me it was “full of bullshit and lies”.

Two weeks ago the Obama administration introduced a fresh twist, when it announced that next year (or in 2011) five Guantanamo Bay detainees will be tried in the same New York courthouse, a few blocks from the World Trade Centre. One of them is Siddiqui’s second husband, Ammar al-Baluchi, also known as Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali, who stands accused of financing the 9/11 attacks.

But while the Guantanamo detainees will be tried for their part in mass terrorism, Siddiqui’s case focuses on a minor controversy whether she fired a gun at a soldier in an Afghan police station. And so the big questions may not be probed: whether the ISI or CIA abducted Siddiqui in 2003, what she did afterwards, and where her two missing children are now.

Judge Richard Berman ruled that Siddiqui “may have some mental health issues” but was competent to stand trial.

Back in Pakistan Siddiqui has become a cause celebre. Newspapers write unquestioningly about her “torture”, parliament has passed resolutions, placard-waving demonstrators pound the streets and the government is spending $2m on a top-flight defence. High-profile supporters include the former cricketer Imran Khan and the Taliban leader Hakumullah Mehsud who has affectionately described Siddiqui as a “sister in Islam”.

The unquestioning support is a product of public fury at US-orchestrated “disappearances”, of which there have been hundreds in Pakistan, and deep scepticism about the American account of her capture. Few Pakistanis believe a frail 5ft 3in, 40kg woman could disarm an American soldier; fewer still think she would be carrying bomb booklets, chemicals and target lists.

But there are critics, too, albeit silent ones. A Musharraf-era minister with previous oversight of Siddiqui’s case told me it was “full of bullshit and lies”.

Two weeks ago the Obama administration introduced a fresh twist, when it announced that next year (or in 2011) five Guantanamo Bay detainees will be tried in the same New York courthouse, a few blocks from the World Trade Centre. One of them is Siddiqui’s second husband, Ammar al-Baluchi, also known as Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali, who stands accused of financing the 9/11 attacks.

But while the Guantanamo detainees will be tried for their part in mass terrorism, Siddiqui’s case focuses on a minor controversy whether she fired a gun at a soldier in an Afghan police station. And so the big questions may not be probed: whether the ISI or CIA abducted Siddiqui in 2003, what she did afterwards, and where her two missing children are now.

In fact the framing of the charges raises a new question: if Siddiqui was such a dangerous terrorist five years ago, why is she not being charged as one now? A senior Pakistani official, speaking on condition of strict anonymity, offered a tantalising explanation.

In the world of counter-espionage, he said, someone like Siddiqui is an invaluable asset. And so, he speculated, sometime over the last five years she may have been “flipped” turned against militant sympathisers by Pakistani or American intelligence. “It’s a very murky world,” he said.

“Maybe the Americans have no charges against her. Maybe they don’t want to compromise their sources of information. Or maybe they don’t want to put that person out in the world again. The thing is, you’ll never really know.”

In the world of counter-espionage, he said, someone like Siddiqui is an invaluable asset. And so, he speculated, sometime over the last five years she may have been “flipped” turned against militant sympathisers by Pakistani or American intelligence. “It’s a very murky world,” he said.

“Maybe the Americans have no charges against her. Maybe they don’t want to compromise their sources of information. Or maybe they don’t want to put that person out in the world again. The thing is, you’ll never really know.”

On July 8, Chief Justice Islamabad High Court (IHC) Justice Muhammad Bilal Khan here directed the ministry of Foreign Affairs to submit its comments regarding developments in the case of Dr Afia Siddiqui for bringing her back to the country. The court sought the response of the foreign ministry after a review petition was filed by the mother of Aafia and Iftikhar Hussain Rajpoot jointly for bringing her back to the country from a detention centre in the US.

Citing former President Gen Musharraf and former PM Shaukat Aziz as respondents the petitioners have alleged before the court that since 1998 after the handing over of Aimal Kansi to the USA, Pakistan has given away more than 9000 citizens in the American custody.

The petitioners have also made the Secretary Interior Syed Kamal Shah as one of the respondents while submitting that he was indirectly involved in the abduction of Dr Aafia, in his capacity as Inspector General Police of Sindh province.

They requested the court to direct the government to take steps for bringing Dr Aafia back to the country, and in case the matter is not resolved, it must be taken to the International Court of Justice under the 1959 treaty that is signed by both the countries.

We need to be absolutely clear that the real issue here is the second set of allegations in which Aafia is victim, not accused.

By remaining silent on that issue now, the whole world is allowing a victim tobecome accused. Since this has already become one of the most famous trials of the new century, a bad precedent in this matter is likely to affect the future of human rights for very long time and almost everywhere in the world. Time is of essence here, because it seems as if evidence is being destroyed very fast.

The following steps may need to be taken without losing any further time:

- Human rights groups in US should file petition in a US court to the effect that Aafia’s trial is unfair and should be dismissed. It needs to be dismissed immediately, and in any case latest by November 7, i.e., 40 days before the date which has been set for hearing whether or not Aafia is mentally fit to stand trial: there is reason to suspect that some foul play is going on which is likely to accomplish its ends by that date and evidence related to actual culprits will have been destroyed, possibly including memory of the victim herself.

- Separately, a complaint should be lodged against culprits who victimized Aafia earlier, and a plea should be made for the recovery of her two missing children.

- All peaceful and healthy means should be used for educating people in as many countries as possible about the AAFIA issue – especially the message that a victim should not be victimized and the meaning of justice should not be distorted.

- Concerned citizens of the world need to explore whether there is a proper channel for taking up this issue beyond slogans, protests and demonstrations. If no such channel exists then it needs to be created.

- If any rights group decides to make a separate committee for pursuing this case, then that committee should also look into the wider implications and related issues, and hence “AAFIA” might be a good acronym for ”Affirmative Action for the Freedom and Independence of All” (Aafia literally means comprehensive safety). Fresh grounds need tobe broken for safeguarding human rights in these new times.

Terrorism is a serious threat which should not be trivialized the way it has been through the victimization of Aafia Siddiqui and her minor children. Genuine efforts being made against terrorism will also earn a bad name, if not fall flat on their face, if moral superiority is lost – and it will be lost if injustice in the case of Aafia Siddiqui completes its course.

The case of Dr Aafia Siddiqui:

The 86-year sentence handed down by a US court to Dr Aafia Siddiqui means the neuroscientist will likely spend the rest of her life in a US jail. In the courtroom, Aafia said she would not appeal the decision, questioning the utility of doing so. The sentence, however, will not bring the Aafia Siddiqui saga to a close. There are far too many lingering questions which are unlikely to ever be answered and which have caused divisions, not only in Pakistan, but even among Aafia’s relatives. We still do not know with any certainty where Aafia was for the five years before she was apprehended by US soldiers in Afghanistan. Her supporters believe she is the “Grey Lady of Bagram”, held without charge at a Nato facility after being handed over to the US by Pakistani agencies. Others, including her ex-husband, believe she was a fully-fledged member of al Qaeda, married a relative of 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Muhammad and plotted against the US. Yet others have suggested even more, saying that she was in Pakistan with the full knowledge of the government.

We also don’t know what became of her children. Their fate remains a mystery with the identity of the eldest boy, returned from Afghanistan, the subject of some doubt. Two of them, according to her family in Karachi, were dropped at her parent’s house in Karachi but we have never been told by whom and under what circumstances. Whatever else may be true or untrue in the strange saga of a young woman who excelled academically at a US institute but is accused of developing al Qaeda links during this time, there can be no doubt her children are innocent and do not deserve any kind of punishment.

As the many supporters of Aafia launch a campaign for her return to the country, we need to also look at the case more rationally. Her involvement with al Qaeda has not been legally proven as it was never up for trial, but the presence circumstantial evidence indicates that, at the very least, she may have materially supported the terrorist group. However, that the US chose not to charge her for terrorism offences shows the lack of legally-permissible proof on this count. That she was never charged for terrorism also adds some fuel to the accusations that she was tortured in custody. Any evidence that the US garnered through torture would not be permitted in court. The ill-treatment Dr Aafia suffered should, of course, never have been inflicted on her. It is obvious she has indeed been subjected at various times to both mental and physical hardship.

The charges against her were limited to the attempted murder of US soldiers. Dr Aafia did herself no favours at the trial and so no one should be surprised that such a stiff penalty was handed down. In open court, she denounced the trial as a farce and even had to be escorted out of the courtroom on two occasions. In addition, cyanide was found in her handbag at the time of the shooting. A psychiatrist declared her legally sane, and despite having the right to stay silent and against the advice of her own lawyers, she took to the stand. She also insisted Jews should not be allowed to serve on the jury.

As a result of public outcry against the sentence, Interior Minister Rehman Malik has requested that the US repatriate Dr Aafia Siddiqui to Pakistan. There are both legal and political problems with this request. The crime for which she was convicted took place in Afghanistan on a US base and involved US soldiers. Other than Aafia’s citizenship, Pakistan has no connection to the case. Furthermore, there is the very real possibility that Aafia will be freed due to public pressure if she is returned to Pakistan. Given the enormity of the charges against her, this could lead to complications. We have already spent two million dollars on Aafia’s trial and possible appeal. It is time to admit she has been found guilty, with plenty of evidence. Taking this any further will show that the government is ruled by emotion rather than political reality.

Organizations make every effort to hire the best and the brightest, yet how many are pro-active in managing those same people to ensure that they have the resources and environment they need to reach their optimal

ReplyDeleteperformance level? It has often been said that people don't leave companies, they leave people, whether it be colleagues or managers or a combination makes little difference to the end result, which is a financial loss of human capital and the opportunities those employees represented.